Definitions

Discrimination

![]()

Discrimination is a phenomenon consisting of unfair and biased differentiation of people due to their personal characteristics, such as, i.a.

- gender,

- age,

- disability,

- sexual orientation,

- nationality,

- ethnic origin,

- religion.

Discriminatory behaviour is defined as behaviour that results in a given person being treated differently than another in a comparable situation.

Discrimination is a form of unjustified, biased and stereotype-based marginalisation of specific social groups which share a specific common characteristic.

Discrimination may concern numerous spheres of our lives (including, e.g., education, employment, business). Each of us can be both a recipient of and witness to discriminatory conduct. It is important to remember that discriminatory behaviour may be highly varied – it can reflect both continuous behaviour directed towards a given person and also specific, formulated phrases, jokes and gestures.

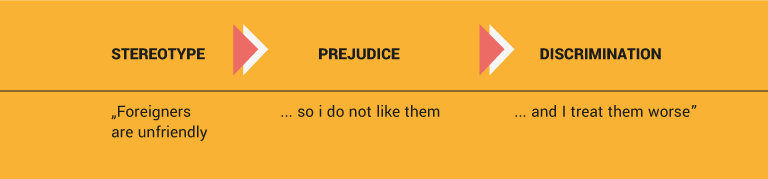

Unequal, less favourable treatment of various social groups sharing a specific characteristic usually arises from prejudices and stereotypes consisting of a simplified, biased and harmful perception of others. Relying on stereotypical, i.e., generalised, fixed and unreasonable, ideas about people with specific characteristics, constitutes the first step towards the development of discriminatory and harmful attitudes in society.

Direct discrimination

Direct discrimination

- It occurs when, due to possessing one or more characteristics, a person is treated less favourably than another person is, was or could be treated in a comparable situation.

- How can we assess whether we have dealt with direct discrimination in a given case? We need to compare the treatment of a person with a legally protected characteristic to the treatment of another person without the mentioned characteristic in a similar situation. Is the treatment the same in both cases?

- The so-called “what if not” test is useful, e.g., “if I were not Roma, would I have been successful in the entrance exam?” or “if I were not disabled, would I have been employed at the university as a doctoral student?”. The answer to the question will enable the determination as to whether or not there has been direct discrimination in a particular case.

- The mechanism of direct discrimination is that the only motive for treating a person less favourably is to see them through the prism of a legally protected characteristic.

See also: An anti-discrimination guide for students and employees at the University of Warsaw

![]()

For instance, direct discrimination results in a wage gap between employees of different gender who occupy the same position and have the same scope of duties.

Direct discrimination at university may be when a lecturer divides students into two groups for an end-term exam according to their age – those under and above 35 years old. Then the lecturer approves the exam of “mature” students, putting a “very good” grade on their exam sheets, and invites the rest of students to write an exam, the results of which determine the grade. In such a situation, students who have not passed the written exam have the right to accuse the lecturer of discrimination based on age.

Indirect discrimination

Indirect discrimination

- It occurs when a seemingly neutral provision of law, criterion or practice causes a person of a given racial or ethnic origin, religion, beliefs, disability, age or sexual orientation, gender, or other legally protected characteristic to be treated in a given situation unfavourably as a matter of fact.

- On the face of it, a seemingly neutral provision of law has nothing in common with the categories of race, ethnicity, religion, disability, sexual orientation, etc. However, its application can result in unequal treatment of a particular group of people.

For instance, a student with a physical impairment asks the departmental authorities to adjust the time for completing written exams due to his mobility by awarding him an additional 60 minutes to take each exam. The authorities refuse the request. In the justification, they refer to general provisions on examination rules, stating that if they want to continue their studies, they have to comply with the requirements for all students in this field of studies.

Harassment

Harassment

- It is any unwanted behaviour that aims to violate a natural person’s dignity and to create an intimidating, hostile, humiliating, or offensive atmosphere for them.

- The concept of “unwanted behaviour” includes both a subjective dimension (as undesirable behaviour by a molested person) and an objectified one (as a “socially unaccepted” behaviour). In practice, this means that we are dealing with harassment also when the person subjected to such action at a given moment does not perceive it negatively, does not explicitly oppose it or even submits to it.

- In the definition mentioned above, violation of dignity may involve different behaviour, e.g., gestures, words, insulting, harassing statements or abusing a given person in any other way.

- It is also worth remembering that any opposition or subjugation to harassment may not bear any negative consequences to such person.

An example of harassment constitutes the following situation. In family law class, a lecturer – discussing the institution of marriage – comments: “There are certain environments that demoralise society by encouraging the legalisation of perversions”. Two students clearly express their indignation by curtly shaking their heads in denial, and one of them stands up and says that, as a gay person, he feels humiliated by such a statement. There is consternation in the room, some students laugh, some of them leave. The lecturer does not react in any way.

Sexual harassment

Sexual harassment

- It is any unwanted sexual conduct related to sex or gender that aims to violate a person’s dignity, in particular by creating an intimidating, hostile, humiliating or offensive atmosphere for them – such behaviour may include physical, verbal or non-verbal elements.

- Sexual harassment may take various behaviour forms, such as inappropriate jokes with a sexual connotation, insinuations, physical touching, obscene comments, emotional blackmail, etc.

- The concept of “unwanted behaviour related to sex or gender” means socially unacceptable conduct. Thus, not only individual protection is provided to the person subjected to sexual harassment, but also the community is protected against behaviour that violates moral norms and is additionally aimed at humiliating another person.

- Even behaviour accepted by the victim, but perceived by others as inappropriate, indecent, embarrassing, and thus creating a bad atmosphere, should not be tolerated, as it violates the principles of social coexistence.

- Similarly, as in the case of harassment, a precondition for sexual harassment is the lack of the harassed person’s consent to specific behaviour and their objection to the abuser.

- Sexual harassment may also constitute a crime pursuant to the provisions of the Penal Code of 6 June 1997 (Art. 197 § 1 of the Penal Code, Art. 198 of the Penal Code, Art. 199 of the Penal Code).

Mobbing (Workplace bullying)

Mobbing

- The distinction between the concept of mobbing and discrimination is a narrow one. Both phenomena are regularly confused. Mobbing victims often face classic manifestations of discrimination; therefore, we have decided to include an example of mobbing in the section ‘discrimination’ (it should be remembered, though, that mobbing is not discrimination).

- Pursuant to the Labour Code, mobbing is defined as any action or behaviour concerning or directed toward an employee, consisting in persistent and long-term harassment or intimidation, which causes an underestimation of professional usefulness, humiliation or ridicule, isolate or exclusion of an employee from the workplace.

- Mobbing includes different types of behaviour aimed at making a given person to feel inferior, excluded, isolated and lose self-esteem.

- Situations in which mobbing occurs may take various forms; hence, mobbing may be unjustified, continuous criticism, mockery, humiliation, ignoring, spreading gossip, forcing to perform more challenging tasks, and assigning tasks that are beyond a given person’s abilities or competency so as to emphasise their lack of professional usefulness.

An example of mobbing is the following situation. Magdalena was employed at a new company. Since she started working, her supervisor constantly mocked her in front of other co-workers and called Magdalena to her office, where she assigned her additional tasks exceeding Magdalena’s competence. The situation lasted for several months and led Magdalena to become depressed, resulting in her spending two months on sick leave.

See also: An anti-discrimination guide for students and employees at the University of Warsaw

Inciting discrimination

Inciting discrimination

A manifestation of discrimination is also an action involving encouraging another person to breach the rule of equal treatment or ordering them to breach this rule. It means that inciting others to act in a discriminatory manner towards others is unlawful, a situation which frequently occurs in the workplace. Refusal to execute a specific command may be related to multiple negative effects on an employee. It should be remembered that we cannot accept all types of orders and commands without question. In such cases, we do not only have the right but are also obliged to resist any acts encouraging a violation of the prohibition of discrimination or which is indirectly aimed at breaching the principle of equal treatment.

One of the fundamental provisions enumerated in several binding legal acts in Poland – both national and international in origin – guarantees legal protection against discrimination. In most cases, they have developed their own definitions of discrimination and unequal treatment.

Practically, examples of acts encouraging a violation of the principle of equal treatment may occur in relations of subordinacy, e.g., in situations where a person has the authority to instruct another or is able to influence their behaviour. For instance, it may be a lecturer-student or university authorities-student relation, in which the decision-making party tries to influence or make a grade or admission to an examination or university dependent on the declaration of discriminatory or negative behaviour towards other students (e.g., due to race, gender, nationality or ethnic origin). A further example of incitement of discrimination is instructing students to prevent other students who belong to national minorities from joining the student self-government.

See also: An anti-discrimination guide for students and employees at the University of Warsaw

Hate speech

Hate speech

According to the Recommendation No. R (97) 20 of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on hate speech, “Hate speech shall be understood as covering all forms of expression which spread, incite, promote or justify racial hatred, xenophobia, anti-Semitism or other forms of hatred based on intolerance, including: intolerance expressed by aggressive nationalism and ethnocentrism, discrimination and hostility against minorities, migrants and people of immigrant origin”.

In essence, hate speech involves negatively characterised statements addressed to a specific individual/group due to their possession of certain characteristics.

Since hate speech is an ever more prevalent phenomenon, special attention is paid to its development in the mass media – on the Internet, in media, in public life and widely defined cyberspace. With the advancement of social media, it is noticeable that ever more frequently we are dealing with people using hate speech; taking advantage of their apparent anonymity, they allow themselves to express hateful rhetoric and contribute to increasing negative attitudes and promoting stereotypes of certain social groups. It is worth remembering that hate speech results in fostering hatred, promoting negative emotions towards a given person/group of persons, is based on stereotypes, discriminatory and humiliating treatment of others; it is not an objective opinion based on facts.

Moreover, hate speech is characterised by lack of tolerance for diversity, promotion of stereotypes and humilitating treatment of others that is often racist or xenophobic in nature. Therefore, hate speech may be (and in fact it is) the first step toward criminal activity (hatred escalation in the form of acts of violence, inciting to commit a crime, etc.). It takes various forms, starting from public incitement to hatred or violence directed against persons due to a characteristic they have (such as gender, race, nationality, sexual orientation, disability, etc.), public dissemination of information, texts, and resulting in offensive or humiliating images/materials about a given person, etc.

It is also often emphasised that hate speech should not be confused with a misinterpreted form of freedom of speech and the right to express one’s own opinions. It is good to have in mind that hate speech fosters hatred, promotes negative emotions towards a given person/group of persons, based on stereotypes, discriminatory and humiliating treatment of others; it is not an objective opinion.

Unfortunately, hate speech is also sometimes aimed at employees and students of higher education institutions in Poland. It takes various forms, starting from public incitement to hatred or violence directed against persons due to a characteristic they have (such as gender, race, nationality, sexual orientation, disability, etc.), public dissemination of information, texts, and ending with offensive or humiliating images/materials about a given person, etc.

Unfortunately, hate speech is also sometimes aimed at employees and students of higher education institutions in Poland. It takes various forms, starting from public incitement to hatred or violence directed against persons due to a characteristic they have (such as gender, race, nationality, sexual orientation, disability, etc.), public dissemination of information, texts, and ending with offensive or humiliating images/materials about a given person, etc.

An example of hate speech is the following situation. A non-heteronormative student X received threats from other students. They were ridiculed, mocked and insulting language was addressed to them in class. After a time, a fake student X’s account was created on a social networking site, where untrue, degrading and vulgar information/images about them was posted. The university authorities and other students did not react to the above situation, explaining that they could not do anything about it and that freedom of speech at the university was guaranteed.

See also: An anti-discrimination guide for students and employees at the University of Warsaw

Discrimination based on skin colour, nationality or ethnic origin

Discrimination based on skin colour, nationality or ethnic origin

It is unfavourable treatment of people solely because they belong to a particular ethnic group, nationality or have non-white skin colour.

The current geopolitical situation, triggered by the Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine, may adversely and inappropriately affect relations within our university community. Strong emotions provoked by the war, such as grief, anger and fear, can arouse stereotypes and prejudices, which can then escalate into unfavourable treatment, conflict and even violence.

They should be monitored rigorously and counterreacted.

![]()

Examples of discrimination based on skin colour, nationality or ethnic origin are the following:

- Refusing the opportunity to participate in events that take place at the University

- Less favourable treatment in examinations

- Dissemination of stereotypical and negative opinions and information on nationality or ethnicity

Inciting discrimination is as reprehensible as discrimination itself.

Micro-inequities

Micro-inequities

In everyday life, we may come across micro-inequities at university.

Micro-inequities express prejudice in everyday interpersonal interactions: small, often unconscious and unintentional, depreciating verbal and non-verbal behaviour that leads to exclusion.

Single and inconspicuous, they may seem insignificant, but when repeated frequently and regularly, they begin to have a cumulative effect – they can result in serious and negative consequences in the working and learning environment.

For example, this includes contemptuously referring to other people based on stereotypes related to nationality, ethnicity or skin colour.

Micro-inequities are revealed in contact with ‘otherness’ – that is, they affect those people who, in a given context, are minority groups, significantly different from the majority, occupying a perceived lower status and lacking agency.

![]()

Micro-inequities can manifest themselves in the following ways:

- Avoidance, silence, ignoring (e.g., not introducing a person at a formal meeting, omitting greetings, not answering a person’s question)

- Laughter, banter, jokes (directly from a given person and from an identity trait they possess, such as nationality)

- Contemptuous comments, interrupting, talking about a person behind their back, not listening to what they are saying

See also: An anti-discrimination guide for students and employees at the University of Warsaw.

Undesirable behaviours

Undesirable behaviour

Any unethical, violent or otherwise unacceptable behaviour experienced by an employee, PhD student or student which refers in particular to competences, position in the team, personal sphere or health.